Recently, while alone and unsupervised, I allowed myself to be goaded into an ill-advised Twitter debate. With someone who calls himself Duck Dodgers, no less. (For those of you who didn’t see it, you can go to my Twitter account, scroll back to April 8-9 and check out this tar baby I got caught up in.)

I soon realized the entire affair was an exercise in futility, so extracted myself from it. It was an exercise in futility because it was a blatant case of the confirmation bias writ large. But my aggravation hasn’t gone to waste because I’ve been waiting for an excuse to write a little essay on the confirmation bias that plagues us all. Who knew fate, in the guise of Duck Dodgers, would give me the prod I needed.

Taktu cleaning fat from seal skin with an ulu Cape Dorset (Kinngait), Nunavut, Canada, August, 1960

In a bit, I’ll describe the details of this Twitter fiasco and how the confirmation bias reared its head. But first, let’s look at provoker-in-chief of the confirmation bias: cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the uncomfortable feeling we all get when trying to hold two opposing or clashing ideas in our brains at the same time.

For example, let’s say there exists a politician you hold in great esteem. You’ve met him in the flesh, and he’s a warm, friendly charismatic guy, who embodies everything you and your party hold dear. Then a credible news report surfaces, fingering the guy as a pedophile.

If this accusation were made against a much-despised politician from the other party, you would have no trouble swallowing it whole. But since it is against your guy, you refuse to believe it. Even as more evidence stacks up, you just can’t bring yourself believe this wonderful person could do such a thing.

The uncomfortable feeling you are experiencing is cognitive dissonance. You cannot hold the idea of this warm wonderful guy who exemplifies your beliefs dandling little boys.

The example above is a bit over the top, but similar, though less extreme, events happen constantly in politics and elsewhere. It is illuminating to see how they are dealt with. How those in power use the resolution of cognitive dissonance to get out of a jam.

Politicians seem to be incapable of staying out of trouble. Of course, they live under the magnifying glasses focused on them by the press and the opposing party, so there is little room for error. When one does screw up, a drama unfolds that always follows the same script.

A news report pops up pointing out a political snafu. The opposing party and its news organs make hay. The offending party is rattled, confused, and lies low until it gets a few plausible talking points put together either denying or minimizing guilt. In rare cases–John Edwards’ impregnating his mistress while his wife, dying of breast cancer, was campaigning at his side springs to mind–the party will sacrifice one of its own. But most of the time, the creation of talking points is the common course of action.

The press and other politicians, of course, all see through this smoke screen. But the smoke screen wasn’t created for them – it was created for us, the great unwashed masses of voters.

When we hear of one of our own screwing up, we are instantly overwhelmed with cognitive dissonance. It’s an uncomfortable feeling. We like this guy, he is in our party, yet it appears he did bad, real bad. How can we hold those opposing thoughts in our brains? We cannot, at least not without considerable discomfort.

But, we don’t have to endure for long because our party leaders’ talking points come to our rescue, especially if picked up and parroted by a complicit media. It’s not really true what you’ve heard, and here’s why. Followed by some explanation of why the reports of pedophilia are false, or simply a smear campaign. Our cognitive dissonance dissolves in the solvent of these soothing words. We don’t have to think. Our man is blameless after all. Life is good once again.

Confirmation bias

The confirmation bias is what allows us to uncritically accept these soothing words as the truth. We’re being told what we want to hear. And, thus, we believe it blindly, willingly, because it confirms whatever we already believed.

To show how the confirmation bias is built brick by brick, let us turn to politics once again.

Assuming we come to politics a tabula rasa (a major assumption because most of us follow in our parents footsteps or openly rebel against our parents), we start at zero.

Imagine yourself at the very top of the pyramid of knowledge and belief. Right at the apex, there is no knowledge or belief. You are a political newborn, so to speak.

At the base of the pyramid, the knowledge level is deep and wide. On the right side of the base all the conservative ideals, knowledge, and insights lie. On the left side live the liberal ones.

When you start at the top, you get tipped down one side or another. Maybe it’s a column you read, or a talking head on TV, or a parent, teacher, or friend. Doesn’t really matter, but somehow you get tipped to one side or the other and start rolling down that side of the pyramid, gathering ideology as you go.

You establish your rudimentary political views, and, as you start rolling down, you read more, you engage in discussion, you watch cable channels that mirror your views, and you, in general, become more entrenched in your ideology. All the way down you continue to confirm your ever-growing bias. Once you have reached the bottom, you have marinated so long in your particular political sauce that you can’t possibly understand how anyone could not believe the same way you do. In fact, you are certain that anyone who doesn’t is a completely misguided idiot.

It never occurs to you that others may have tipped and rolled down the other side of the pyramid. They, too, have reached their side of the bottom and are completely infused with the righteousness of their own beliefs and cannot imagine how someone could be so stupid as to believe any differently.

What is even worse is that many of us who have rolled down our own side of the pyramid refuse to even read anything written by one who has rolled down the other side. You don’t want to learn anything that might throw you into cognitive dissonance, so you renounce it as trash, unworthy of your reading, and move on. We’ve all done this at some time or other.

We work hard never to let opposing views penetrate our consciousness in an effort to avoid the unpleasant sensation of cognitive dissonance. The confirmation bias is the tool we use.

Conservatives don’t watch MSNBC; liberals don’t watch Fox. We always subscribe to magazines and newsletters that reflect our own underlying views. We read blogs that confirm our biases. If we stumble on one that doesn’t, we often leave snide comments and never return. The wide variety of material available on the internet and cable TV today is, in my view, why politics is so vicious. Not all that long ago, most of us had access to a daily newspaper or two and three TV channels, all of which were moderately liberal. People could argue with one another and drift toward the extremes, but were almost invariably brought back toward the middle by the staid mainstream media. Now people can indulge their confirmation biases 24/7, which doubtless leads to more edging toward the fringes and less trust of those on the other side of the debate.

Whenever someone comments for the first time on this blog and has a website (which can be discerned by their name being hyperlinked), I will often click on to take a look. If the commenter turns out to be a liberal, his/her website will be crawling with countless links to other liberal blogs, newsletters, articles, etc. Same if a commenter is conservative. I never find a blog of a political nature (save one, see below) that has links to both conservative and liberal sources.

You can test your own confirmation bias by going to one of my favorite sites, RealClearPolitics.com (RCP), the blog mentioned above that does link to both liberal and conservative sites. Go to the site and read down the list of hyperlinked articles. Some days it’s a little more conservative than liberal, and other days it is just the opposite. But on any given day, the site serves up a pretty even mix.

As you let your eye run down the list, notice which ones you want to open and read versus the ones you want to avoid. If you are a liberal, you will doubtless be drawn to those articles that confirm your liberal bias, and you will avoid opening and reading the obviously conservative ones. Same thing if you are a conservative.

And, God forbid, if you are a liberal (or conservative) and you happen to click on a link you think will confirm your bias only to discover it does not, chances are you will call BS and back out of that turkey in a heartbeat.

As an exercise in exorcizing my own political confirmation bias, I several years ago made the commitment that if I went to RCP, I would read every article. Not pick and choose. It has been quite enlightening.

We should all do this, not just with politics but with everything. Many aspects of life plunge us into cognitive dissonance, and our good friend and enabler, the confirmation bias, always stands ready to help us out of it. It takes real work to hold the confirmation bias at bay and think critically. Critical thinking efforts are difficult and do not always provide us with the answer we want or sometimes even the correct answer, but they are, as Freud said of women, “the best thing of their kind that we have.”

The confirmation bias is everywhere

Sadly, our tendency to succumb to the confirmation bias is not limited to politics. Even scientists are all too prone to fall victim.

I would say at least half, if not three fourths, of papers published in academic journals are exercises in employment of the confirmation bias. It’s even worse with non-academicians, bloggers and the like, who truly (if sometimes mistakenly) believe they are practicing good science and indulging in heavy duty critical thinking.

I want to use my recent Twitter dustup with Duck Dodgers as an example of what I mean.

Here is the set up.

A blog post appeared, crediting Duck Dodgers for most of the content, stating in no uncertain terms that the Inuit were not in ketosis, and so therefore the Inuit didn’t really eat a high-fat, low-carb, ketogenic diet.

The basis for this unequivocal pronouncement were three old papers published between 40 and 85 years ago. The authors of these papers had not been able to find measurable ketones in their Inuit subjects under normal conditions. After a day or two of fasting, however, ketones were present just as they are in most of the rest of us. This finding set the authors to speculating as to why a group of people who ate primarily fatty meats would not be in ketosis all the time, because it just didn’t make sense that they wouldn’t be throwing off ketones like crazy.

One proffered solution to this conundrum was that the glycogen in the meat providing the bulk of the Inuit diet was providing enough carbohydrate to prevent their going into ketosis. It was known then that glycogen (the storage form of glucose) was present in muscle, and it made sense that there might be enough glycogen therein to prevent ketone formation.

There is about 6 grams of glycogen per pound of meat, so if the Inuit consumed from five to eight pounds of meat per day, as the articles claimed they did, the 30 to 48 grams of glycogen could conceivably halt ketone production. Especially if there were a bit of plant or vegetable matter thrown into the mix. That was the speculation at any rate.

The fly in the ointment here, however, is that glycogen rapidly degrades into lactic acid upon death. So unless this meat came from living animals that were still breathing while being eaten–highly unlikely–there wasn’t any glycogen to be had.

Scientists working today use liquid nitrogen ( ?320F) to flash freeze the livers and muscles of sacrificed lab animals immediately after death in order to determine the glycogen content before it degrades. Scientists working 80 years ago didn’t have this option, nor, apparently, did they understand how quickly glycogen degrades.

Glycogen degrades to lactic acid post mortem

What happens is this: when an animal meets a sudden end, it doesn’t die all at once. It’s kind of like a modern car. You pull it into the garage and turn off the key, but the lights stay on, the fan keeps running, the windows can still go up and down for a bit. The car is dead in that it has no way to actually run, but parts of it are still alive.

If, God forbid, you were to be shot in the heart with a high-powered rifle, you would doubtless be dead. But, like the car in the garage, parts of you would live on for a while. The muscles in your legs, for example, wouldn’t know you were really dead, and they would keep on keeping on.

In order for muscles, even relaxing muscles, to survive they need to burn fuel. Burning fuel requires oxygen. If your heart isn’t pumping because a bullet went through it, the muscles in your legs get no oxygen. When no oxygen is available, muscles do what muscles do when they exercise intensely and can’t keep up with the oxygen demand: they switch to anaerobic metabolism and go after the stored glycogen.

Burning the glycogen anaerobically results in a buildup of lactic acid. When your muscles are exercising, the blood washes away the lactic acid, but even then, if you exercise intensely enough, the lactic acid build up outpaces the blood’s ability to carry it away, leading to lactic acidosis. Your exercising muscles begin to burn and if you don’t slack off and let the accumulated lactic acid get washed away, your muscles will begin to cramp.

Same thing happens when you are dead. Since there is no blood pumping oxygen to the muscles, they burn glycogen anaerobically, producing lactic acid, which accumulates. Ultimately, the glycogen is depleted, the tissues are acidic, and no more ATP is produced. No more ATP means no power to run the calcium pumps, the cells lose calcium and the muscles begin to contract, leading to the condition called rigor mortis.

The upshot of all this is that when animals die, the glycogen in their muscles quickly degrades to lactic acid. The only way this process can be halted is to immediately flash freeze the tissue with liquid nitrogen to halt the glycogen to lactic acid conversion. Since that happens mainly in the lab and in special flash freezing facilities, any meat you purchase at the store or from your local farmer or that you kill yourself will not contain any glycogen to speak of.

The glycogen to lactic acid conversion upon death is all really basic science, not in dispute by anyone.

Keto adaptation

Then along comes the Duck claiming the glycogen survives death and is really there, which, he believes, is why the Inuit, under normal circumstances, don’t have measurable ketones. They’re eating all this meat, which is full of glycogen. What he fails to understand is that the Inuit are keto-adapted. Their lifelong diet of high-fat meat has gotten their ketone-producing-and-consuming systems working in precisely controlled fashion. Like, dare I say it, a well-oiled machine.

The Inuit burn ketones as they make them, so it stands to reason that they might not have measurable ketones under normal circumstances. During the time these old studies were done, the non-Inuit, white-bread-eating, white man was the standard. Feed a non-keto-adapted bread eater the Inuit diet, and he goes into ketosis in no time. Researchers back then figured the Inuit should do the same thing, and when they didn’t – because of keto-adaptation, which was not understood at the time – these scientist thought it worthy of publishing.

I gently pointed this out via Twitter and generated a barrage of Tweets from the Duck, consisting primarily of a series of links to obscure documents showing there was indeed glycogen in meat. Especially meat that had been quickly frozen. There were anecdotes about fish, having been jerked from holes in the ice and exposed to air, freezing instantly. I responded that it didn’t matter how cold it was at the Arctic Circle, it wasn’t -320F, which is about the temp of the liquid nitrogen required to freeze tissue quickly enough to preserve glycogen.

Stefánsson makes an appearance

I proposed a reading of some of the works of the arctic explorer Vilhjálmur Stefánsson, who had lived among the Inuit for years and knew their ways well. He had described their eating habits in many of his books and articles. This suggestion inspired another over-the-top post, with content credited to the Duck, describing Stefánsson as a charlatan, a humbug, and a poltroon, who couldn’t be trusted to get anything right. (Stefánsson was involved in a couple of controversial events–the loss of the Karluk and the Wrangle Island expedition, both of which resulted in the loss of life. If Stefansson had fault in these, it arose from his overestimating the skills of those others involved. He, himself, was an intrepid Arctic explorer, who was never daunted by cold, barrenness or distance. And, as far as I know, no one ever doubted his observational ability in terms of the ways of the Inuit.)

I responded with a link to Stefánsson’s obituary appearing on the front page of the New York Times on August 27, 1962, which, though it did make reference to the Wrangle Island fiasco, made no mention of any skullduggery on his part.

I was then accused of not using science to argue my point, but resorting to nonscientific articles in “news rags” to bolster my case. I pointed out there was no science involved in repeating accusations of Stefánsson’s alleged humbuggery, and all I was doing was noting the most prestigious newspaper of the time, a newspaper never afraid to state the bad along with the good in an obit, ran a front page obituary without any mention of these accusations, leading me to believe they were not widespread and in common knowledge. Everyone in the public eye has detractors–for example, Christopher Hitchens wrote an entire book damning Mother Teresa. Had Stef been the vile lying swine the Duck was making him out to be, I doubt the NY Times would have treated him so kindly.

After a little back and forth, I withdrew from the debate, because it was becoming a bit harsh. Twitter is kind of the internet Wild West today, and many less restrained Twitterers were jumping into the fray, and the attacks were becoming too ad hominem for me.

Soon, the Duck bailed out, too, but not without recasting his views in a long farewell comment.

I thought the whole thing had come to its end, when someone wrote a comment attacking the Duck for attacking me. Duck responded by fisking his tormentor’s comment.

Parts of a couple of paragraphs provide a perfect example of what I mean by the confirmation bias and is emblematic of the way most people argue a point today:

I hope you realize that Dr. Eades isn’t an expert in everything. I did a lot of research and simply showed Dr. Eades numerous studies that showed he was mistaken. I don’t see what the big deal is. [Italics mine]

I put a lot of research into this article, citing over a dozen scientific studies to support my case. When he outright dismissed the article, I continued to show him real world evidence on Twitter and scientific data that explained why he was mistaken. Dr. Eades never once showed any scientific evidence to refute anything I put forward. [Italics mine]

I am absolutely certain the Duck put a lot of time in on his research, but he went about it in the wrong way, and the confirmation bias jumped up and bit him in his tail feathers.

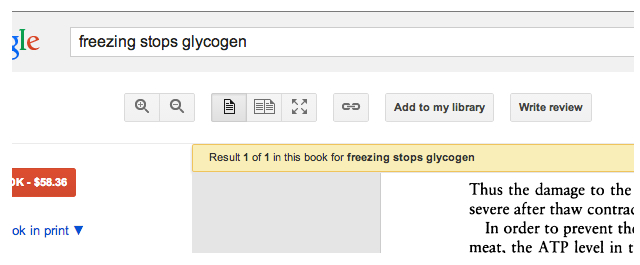

I know this to be true from one of his Twitter links. Take a look at this screen shot:

If you look at this link purporting to be real science bolstering the Duck’s case, you’ll see the Google search terms he used to track down this article were “freezing” “stops” “glycogen.” He wasn’t making a serious scientific inquiry–he had already gone public with his theories, now he was simply looking for anything to confirm them. The sad thing is, in Googling those three words, Google presented Duck many pages of material, most of which confirmed the basic science view of the degradation of glucose to lactic acid immediately post mortem, before he ever got to the page pictured above confirming his bias. Try it yourself. Google those three words and see what you find.

That’s not how science works. In real science, which is, sadly, not practiced all that often, researchers attempt to discredit their hypotheses, not confirm them. Only after repeated efforts to prove their own theories incorrect, do true scientists start to consider that they may be on to something.

Most researchers, however, are like the Duck. They come up with an hypothesis, then construct an experiment designed to confirm what they think they know. And they usually do.

But let me end this interminable post on a conciliatory note. Let us grant the Duck the glycogen he swears the Inuit get from eating their five to eight pounds of raw meat per day. There is about 6 grams of glycogen per pound of raw meat, so if you want to eat five pounds of raw meat per day to get your 30 grams of carbs, go for it. I still say it is a ketogenic diet, and I’ll bet good money that until you become keto-adapted, you can eat all the carbs you’ll find in your daily ration of five to eight pounds of raw meat and still turn your ketostix purple most of the time.

If only this were the kind of ‘high-carb’ diet most people followed, we would have a lot less disease and a lot fewer victims of obesity.

If you would like to read more about cognitive dissonance and the confirmation bias, I can recommend two excellent books. Mistakes Were Made and When Good Thinking Goes Bad. Both are excellent.

Photo Credit: BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives via Compfight cc

I witnessed that exchange and it was kind of the final straw for me. Many a blog now I simply don’t read anymore, FTA included. Resistant starch is interesting, but one can only take so much. Unfortunately one after the other LC blogger is heading in that direction. Fat Head’s the latest it seems, judging by Tom Naughton’s comment:

“[…] I’m moving towards more of a Perfect Health Diet. I didn’t have the high fasting glucose issue that Richard wrote about, didn’t have the dry eyes, cold hands or thyroid issues that some people report on VLC, but his posts [Tim Tatertot’s] about RS and gut health convinced me it’s important to feed those gut bugs … and I’d rather start before I develop a problem.”

I’m well aware of my own confirmation bias, but I simply accept that as part of life. Can’t really get around it. I fully accept that I may be wrong, but really, some of us do fine on LC – unlike the claim on FTA that 100% of low carbers will develop autoimmune issues. C’mon, 100%, that’s nuts.

I began following FTA to learn more about resistant starch and ultimately ended up confused about the food choices Richard was making. He would post his blood glucose numbers after eating rice and other carbs while on resistant starch; he would get what I felt to be poor numbers while he seemed to think they were great.

I posed the question why was he using resistant starch as a “get out of jail free” card for making what I would consider to be poor food choices. Why eat foods we probably shouldn’t be eating (for a variety of reasons) when the blood glucose advantage still wasn’t that great? His response was rude and not at all helpful – I haven’t been back to his site.

But I have added resistant starch to my diet just to see what it does. Just because Richard is a jerk doesn’t necessarily mean resistant starch might not have benefits.

I agree. Not necessarily about Richard’s being a jerk but about the notion that there may be some benefit of resistant starch. I just don’t like to jump headfirst into stuff until it gets sorted out a little better. When I first went into medicine, I was an early adopter. I gave patients all the new drugs that came along. Until there were a few bad outcomes, which made me a lot more conservative in my approach and got me off the early-adopter bandwagon, at least where treating patients was concerned.

For this reason, it takes a while and a lot of data before I jump ship and plunge into the latest new and exciting remedy.

If we could all adopt such type of thinking! However, I believe that our egos and the fact that we want to be right all the time is what fuels these debates, if we can call them like that.

It’s kind of difficult to have a hypothesis and try to prove it wrong. I mean it’s difficult for most “researchers” since as you said, most of them try to find the right arguments to make their hypothesis stand tall.

I recall that some friend said that’s easy to do research today:

1. develop a hypothesis

2. go to pubmed or google scholar and search for data to prove it right…

Damn, when are we gonna learn to think critically?

Sad but true. That’s how it’s often done.

Well, anyone who has made too many potatoes or too much rice for dinner and eats it the next day, is eating “resistant starch” whatever that means. Putting a scientific schnozel on simple leftovers only creates a new bandwagon for everyone to jump on. After a galloping good ride, there will be a new one to climb on.

The best dietary advice I was ever given was: If it wasn’t in your grandmother’s kitchen, don’t eat it.

BTW, the Yiddish word I was looking for means “big nose.” Anyone help me out here?

I think the word you’re looking for is “schnozz.”

When invoking images of paedophiles to colour your prose, is it really appropriate to use descriptors such as “fingering” and “swallowing it”? It seems unnecessarily gratuitous..

lol If “fingering” and “swallowing it” bring images of pedophilia to mind, I think that may say more about YOU than Dr. Mike. While both could be taken in a sexual context, why that sexual context would be assumed to include children first speaks to your own mindset while reading.

Great stuff Dr Eades, as usual. If ketogenic diet does not work for me or I don’t have a clue how to adapt properly it does not mean I should try very hard to make everyone else believe that there is no such thing as ketogenic diet.

I was curious to know what these people were saying, so I went to a couple of the links. I soon gave up. Why? I hope it wasn’t just confirmation bias.

The problem I found was that people don’t define their terms. For example, how was “ketosis” determined? By acetoacetate in the urine? By BHB in the blood? You can have the latter without having the former. But earlier researchers didn’t have ketone meters to enable measuring BHB in the field.

So subjects might have lacked ketones in urine and conclusion was that they weren’t in ketosis. And these studies are cited as proof.

Also, “eskimos” are not all the same. Coastal eskimos ate a lot of seafood; inland eskimos ate a lot of caribou. Diet varied during the year.

Some people claim that “eskimos” got carbs from eating mossy contents of caribou stomachs and others say “eskimos” gave the stomachs to the dogs. Then there is the problem that Margaret Mead found, that subjects being studied often tell the researchers what they think they want to hear.

Yet people will make blanket statements like “eskimos aren’t in ketosis” on the Internet, and this will be reposted and accepted as truth when it’s basically meaningless.

It’s difficult enough to ferret out the truth, given all the variables, and it’s sad when time and space are devoted to supporting one dietary worldview on the basis of inadequate understanding and a lack of clarity about experimental conditions.

Another variable is that we may have slightly different metabolisms for genetic, as well as dietary, reasons. For example, salivary amylase copy numbers. So if one blogger feels terrible on a LC diet, probably that individual should not follow a LC diet, but it doesn’t mean no one else should.

I think a LC diet is the best place to start, especially for anyone with type 2 diabetes or a weight problem and metabolic syndrome (probably a high percentage of middle-aged Americans). If that doesn’t work for you, for whatever reason, then try something else.

It’s good that the Internet has made so much science research available to everyone. It’s sad that so much of that research is misinterpreted and used as “proof” of preconceived ideas.

+1

Really excellent article, Michael.

This in particular strikes a chord with me:

That’s not how science works. In real science, which is, sadly, not practiced all that often, researchers attempt to discredit their hypotheses, not confirm them. Only after repeated efforts to prove their own theories incorrect, do true scientists start to consider that they may be on to something.

Most researchers, however, are like the Duck. They come up with an hypothesis, then construct an experiment designed to confirm what they think they know. And they usually do.

___________________________________

This kind of “science” has infected so many areas of interest. Climate science in particular (in addition to diet/nutrition as you’re well aware) is teeming with it, and it’s then being used to try to increase govt power and influence over us. It’s pernicious.

Pernicious, indeed. And widespread.

Made worse because there is now so little independent/government funding for true research. Those with the big money can buy the “science” they want to refute anything that would hurt their bottom line. And, because of these inbred biases people can for some time be led to ignore anything that don’t really want to hear.

Duck isn’t the first amateur researcher claiming to be a “real scientist” (naming no names, here)…. the worst part of the problem, though, is that professional researchers are frequently just as bad. 🙁

I absolutely agree.

Some researchers (e.g. Dr Hugo Mercier, look him up on Google Scholar), argue that the confirmation bias isn’t a defect of human reasoning. In fact, the opposite is true – at least in social contexts, the confirmation bias is a positive feature.

Here’s how it plays out in the real-world. We use our confirmation bias to generate an arguments (“RS is the bestest thing ever!!”). Indeed, we stubbornly stick to that argument and seek supporting evidence, never contradictory evidence. This is easier than reading all of PubMed to decide on the truth. We are not robot automatons.

This seems like a misdirected route of finding the truth. But wait. We are social creatures. Evolution has us primed to to reason in social contexts, not alone. So what happens is, one’s peers and colleagues can critique your argument (which you generate via the confirmation bias). We are far better at critiquing the arguments of others’ than our own. This is why peer-review and open-criticism is so crucial in the scientific method. It is dangerous to reason alone; the (social) context matters. We are not objective towards our own arguments, but we do show profound cognitive vigilance towards the arguments of others.

I hope that makes some sense. Anyone interested should read or listen to some of Hugo Mercier, as he understands human reasoning far better than I do. It just irks me when people say the confirmation bias is a defect of human reasoning. It isn’t.

Thanks for the heads up on Hugo Mercier. I wasn’t aware of him or his work. Thanks to Google Scholar, I found a few papers to pull, which I will dutifully read. I love his description of “our pig-headed core,” the older part of reasoning apparatus. I’ve always referred to it as the reptilian part of the brain.

I haven’t read Mercier’s work yet, but I’m not entirely sure I totally agree it as per your description. I do think the confirmation bias plays a useful role sometimes. But I’m not so certain it’s a good thing in, say, peer review. In fact, I think it’s a real problem. What happens is this: A new paper gets submitted, and the editor of the journal sends it to peers to review. In deciding which peers to review the paper, the editor has two choices: he/she can send it to researchers who have written similar papers and understand the particular brand of science the paper represents, or he/she can send it to ‘peers’ who understand the science, but have written papers expressing opposing views. If the paper gets sent to the first group, it will get an easy pass because it fits with the bias of that group; if, however, it gets sent to the second group, it will likely be deemed unfit to publish and rejected because it flies in the face of the bias of the members of the second group, and they consider it bad science, unfit to see the light of publication. Which is why so many crappy or tepid articles get published. Either they fit with the bias of the reviewers or are innocuous enough not to ruffle any feathers. Of course, it doesn’t happen this way 100 percent of the time, but it does frequently enough.

I think knowing about the confirmation bias is important. We all have it and, if we consider ourselves critical thinkers, should guard against its often pernicious effects.

I love the little book I recommended at the end of the blog because it was written by a professor who teaches critical thinking and is full of references for further study. And, best of all, it describes a number of his battles with his own confirmation bias, showing how, once he made the decision to critically think instead of simply knee jerk react to something he ‘knew’ was true, he discovered how wrong he had been all along. Critical thinking is a difficult tool to learn to use, but once mastered (to the extent anyone can really master it), brings much enlightenment.

Did you Google “Hugo Mercer lying fraud bastard” or just “Hugo Mercer”

Just Hugo Mercier. Should I re-Google? 🙂

Ok, please write on the hottest topic now! 🙂 Resistant Starch! It seems too good to be true! I, for one, love potato salad! 🙂

Always remember the old saying about anything that seems to good to be true…

Beneficial beyond dark chocolate and onions/garlic and other non starchy veges that actually taste good?

As an ex carbivore cold potato would have to be by far my least palatable option well excluding raw.

And what benefits exactly compared to my current great health and lean body composition?

“Feed a non-keto-adapted bread eater the Inuit diet, and he goes into ketoses in no time”. Is it ketoses for plural or ketosis?

It’s not the plural. It’s a typo. All fixed now. Thanks for the heads up.

This is true. I had a doctor who women thought was cute, but he dismissed me from the practice 2 days after alleging a HIPAA violation to the authorites (retaliation is illegal), missed complications after a surgery, sent me to a doctor that all of a sudden after I was dismissed, couldn’t find anything wrong but couldn’t diagnose me even with medical research given to him, gave me a “mental diagnosis” that didn’t match the DSM IV criteria for the disease, and then dismissed me when I said I couldn’t pay him for an office visit.

Do you think any one believes the records, the medical research, phone logs, etc.? Oh he’s cute …

You’re post is right on.

I would dismiss you too.

Nice post (and great vocabulary), Dr. Eades.

Do you think there is merit in contesting the claim that a diet containing five to eight pounds of raw meat daily is a ketogenic diet because of the amount of protein it contains?

Well, there is raw meat and there is raw meat. I doubt that anyone – the Inuit included – who eats five to eight pounds of raw lean meat per day. Lean meat contains about 7 grams of protein per ounce. Five pounds would give you about 560 grams of protein, which is a lot. The Inuit eat fatty cuts of meat, which provide more calories from fat and fewer from protein, so they don’t get anywhere near the protein intake they would were they eating lean meat.

If you want to read some pretty good pieces on the protein/ketosis issues by a nutritional biochemist, check these out (here and here).

Thanks for the links, Dr. Eades.

I would imagine that if you assumed that the Inuit are getting 1/2 the protein you estimated (cool aside: nutrition data is available for polar bears and bearded seals), Dr. Phinney (who was cited a couple of times in one of the links) would argue that a protein intake of > 3g/kg/d (280g protein for a 170 lb. individual) is not part of a well-formulated ketogenic diet. I’m not sure if he’s done the studies, or studies exist with protein intakes in the higher ranges (not sure what that means, but let’s say > 2g/kg/d), but would be interesting to see if it suppressed ketones.

I certainly wouldn’t personally clock measurable ketones eating several pounds of meat per day, either fatty or high protein. Whether this is a result of the protein or the lack of a calorie deficit I don’t know, but with three methods of measurement (blood B-OHB, urine AcAc, breath Acetone) that’s my n=1 experience.

Glycogen in muscles does deteriorate fairly quickly after death which is why databases don’t report carbs in meat (especially those from outside the USA where carbs are actually *measured* rather than guessed by subtraction). On the TV last night it showed how electric shock is applied to recently killed carcasses to speed up the process by twitching the muscles.

During exercise wouldn’t it be lactate that builds up, not lactic acid?

No, it’s lactic acid. You can read all about it here.

In biochemistry, -ic acid and -ate are closely related. The -ate is the conjugate base. I have to admit, I’m not yet fully clear on the significance of that myself.

You might like this cartoon (which I found via confirmation bias methods): http://books.google.com/books?id=8a0Q3LPL1vgC&pg=PA12&lpg=PA12&dq=-ate+-ic+acid+conjugate+base+lactate+lactic+acid&source=bl&ots=Cw5wCdW1pq&sig=7DE7UcDAu10Py3bhd7YaKsyuHmo&hl=en&sa=X&ei=vixUU_uJEsuMyAGgvoGwBQ&ved=0CGAQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=-ate%20-ic%20acid%20conjugate%20base%20lactate%20lactic%20acid&f=false

Yep. Maybe we an just call it a hyperprotomic solution as suggested.

Post mortem, it’s definitely lactic acid since the pH drops with time.

Lactic acid is hydrogen lactate, to propose an alternate lactate you need to specify what the cation is. As muscle goes acidic in rigor mortis my vote is with the hydrogen.

Great article, I really appreciate you putting the time in to address it.

Thanks. I appreciate your kind words.

Wonderful post.

I used to read FTA years back; now it’s just how I imagine asylums were before Haldol.

And the relentless starch justifications sound a lot like, “It’s not enough that I eat Taco Bell; everyone else must line up behind me in the drive-through.”

Dr.Eades, you discuss the style of argument, but I was hoping you would address the counterarguments that were made. You’ve repeated or clarified the points you made at the beginning and thank you for that, but those points were countered and I have not seen those counterarguments being addressed.

If you get a chance, would you address these please? Because I’m sure I’m not the only reader now confused :

1._The inuit were not in ketosis because the large amount of meat they ate has both some glycogen and a great deal of protein, upwards of 200gm. Also, the coastal groups had meat from marine mammals that contains large amounts of glycogen, while inland groups had meat ‘fermentation’ methods that increased carbohydrate content.

However, even if the higher glycogen content weren’t true and they weren’t getting more than 50gm of glycogen from their meat, the high protein itself stops ketosis?

The other points that I can see are minor compared to above since they only deal with details about glycogen :

2. __the time it takes after death to deplete glycogen is at least several hours and can be a couple of days, as illustrated also by slaughter house and/or meat packing methods that aim to accelerate this process.

3. __the temperature that Best preserves the original state of the meat or any biological sample (eg. preserves the most glycogen and for the longest time) may well be liquid nitrogen, but higher freezing temperatures are bound to preserve some too because the process scales with temperature, it’s not a switch that clicks at -196C.

I’m trying to follow the debate and appreciate any help on this. Thank you.

If the Duck were arguing that the effects of gravity didn’t apply to the Inuit, would I be expected to counter those arguments? It’s all really basic biochemistry we’re talking about here. Not some new and exciting scientific discovery.

Think about it, if there are 6 grams of glycogen in a pound of raw meat on the hoof, and only half of it degrades during the slaughter, butcher and refrigeration process, would that 3 grams per pound keep me out of ketosis? Have you ever eaten a pound of raw meat? I have, and it ain’t easy. Unless it’s steak tartare, which is chopped up into little pieces and mixed with spices.

Take a look at these two posts by a very smart nutritional biochemist. (Click here and here) All of your questions should be answered.

Oh dear, I think biochemistry is quite safe. I did not see the Duck ever arguing whether it applies to the Inuit.

The only question seems to be how much fat did the Inuit eat versus carbs-plus-protein, since that would allow at least an inference about ketosis.

The only direct evidence, ketone measurements, is all against ketosis. There were no other direct measurements ever made that actually showed them in ketosis, were there?

If not, there can’t be any confirmation bias regarding the direct evidence, ketone measurements.

Therefore, it comes down to an argument about diet composition.

Any research showing an Inuit diet composition favorable to ketosis would be indirect evidence and would have to be weighed against the evidence opposing it.

At least though it would be evidence that is being discussed.

About that diet composition :

From the glycogen amounts that you quote, you seem to be saying that they did not eat organs or blubber or any additional sources of glycogen/glucose or sources of other carbs, only what’s found in muscle meat.

There is evidence for this? If not in the Inuit, in other H-G groups?

Are you also saying that even with all the extra protein they were getting from the large amounts of meat they ate, they would still be in ketosis?

Isn’t a ketogenic diet designed around the ratio of fat : combined (protein+carbs) ?

Biochemistry is grand, I’m rather partial to it myself and chose it for my minor in undergrad. My Ph.D. thesis was on organic materials.

I also love steak tartare, more so with a raw egg on top! I don’t love politics or assorted biases.

Thank you for getting back to me.

Based on my reading, the Inuit ate a diet high in fat and moderate in protein and lacking in carbohydrate. Such a diet is a ketogenic diet by the standards of the non-Inuit research subjects typically put on ketogenic diets for study purposes. As far as I know, we don’t have a plethora of study subjects who have been on such diets their entire lives, so we don’t know how they would react. We do have the papers quoted in the blog post I linked to showing that the Inuit, on the typical Inuit diet, aren’t in ketosis. We can interpret this info in several ways. We could say that the measuring techniques used at the time were not sophisticated enough to measure the low-level of ketones in the blood of people who are ketoadapted. We could also say that perhaps the Inuit, after a lifetime of ketoadaptation, have levels of ketones that aren’t measurable because they have a lifetime of adaptation. Or we could posit, as the Duck does, that there is enough glycogen in the high-fat, meaty diet the Inuit consume to prevent them from going into ketosis. In other words, they aren’t ketoadapted – they’re consuming a high-carb diet. Not a 300 gram per day high-carb diet, but a diet high enough in glycogen-derived carb that ketosis is prevented. Of the three scenarios above, I believe the last is the least likely.

Why? Because when non-Inuit go on such a diet, they go into ketosis. Therefore there isn’t enough glycogen in the fatty meat the non-Inuit eat to prevent ketosis, so why would it prevent ketosis in the Inuit?

Thank you for laying that out, including the basic premise of the diet composition.

I can see that if the diet was “high in fat and moderate in protein and lacking in carbohydrate”, then all the rest follows rationally.

So really the issue is about that basic premise, about whether the diet was ketogenically high in fat compared to protein+carbs.

I see that premise is what is used in the relative ‘weighing’ of the three scenarios, including against the direct ketone measurement evidence, which can then be discounted due to keto-adaptation.

That adaption can be invoked if the basic premise for a ketogenic diet is true.

Here’s my problem: the only direct documentation quoted has the Inuit eating 5 to 8 lbs of meat a day, as you’ve noted in your post.

That’s too much protein for a ketogenic diet.

Also, any kind of high meat consumption ruins keto ratios even more when added to the various small (but cumulatively substantial) sources of glycogen and other carbs that have been cited.

What can fix the ratio of course is if there’s research documenting a High fat and Moderate protein diet (so, a much lower meat content?).

Otherwise, to support a ketogenic conclusion I would have to say :

_ I don’t believe the cumulative sources of glycogen and carbs (argue about indirect evidence)

_and I don’t believe the Direct evidence of ketone measurements (ok., there’s a physiological argument against them, based on the diet composition premise)

_and finally, I also don’t believe the Direct evidence (documentation) of high-meat diet composition.

So, I would have to discount all the direct evidence on the Inuit diet and ketosis and that leaves just an argument about the relative amount of carbs ?!

Unless, as I’ve noted, that’s Not all the direct evidence.

However, I haven’t found any reference documenting anything other than high meat consumption.

Do you have any references documenting moderate meat/protein consumption in the Inuit?

Or is the diet composition premise an inference from synthesizing various indirect sources of information on their diet, environment etc?

The nature of evidence would change the argument, wouldn’t it?

Lightens idea of ‘confirmation bias’ maybe? 🙂

Thanks again.

I don’t think the Inuit ate five to eight pounds of meat per day. And I’m not sure that the protein in a lot of fatty meat would interfere with ketosis. Why would it? The liver converts protein to glucose as the body needs it – it isn’t substrate driven. In other words, more protein doesn’t necessarily mean more glucose. Insulin controls gluconeogenesis, and it is known that protein stimulates the release of insulin. The insulin will inhibit gluconeogenesis.

“The liver converts protein to glucose as the body needs it – it isn’t substrate driven.”

I was going to say that. It is a very salient point as many seem to be under the impression that it is substrate driven. I believe Amber wrote on that issue, too.

That’s the crux of it : why discount the documentation of high meat consumption?

As for protein interfering with ketosis, I see there may be a biochemistry/physiology argument there?

There’s a lot of anecdotal evidence, most famously I guess at LLVLC(!) , that too much protein won’t let you drop into ketosis and there’s the epilepsy/John Hopkins hospital diet prescriptions for ketogenic diets that lump protein+carbs together and focus the ratio on fat, eg. 4:1 F:(P+C).

I thought such ratios derived from the hormone signaling, basically the glucagon/insulin ratio to drive gluconeogenesis vs. glycolysis.

Also, on another level, it makes sense when considering that ketone production ramps-up in order to lower gluconeogenesis, saving muscle protein in starvation (I believe you mentioned that again just recently somewhere in these comments too). However, excess protein ingestion eliminates the need to get amino acids from muscle, so then there’s no need to lower gluconeogenesis and no increase in ketone production.

Peeling away at this, I’m reexamining basics. I play devil’s advocate in order to be able to do that effectively, in fact, to avoid confirmation bias 🙂 . So thank you for engaging.

I’m not certain that high meat consumption is documented. Both Stefansson, who spent many years living with the Inuit in the early 1900s and John Murdoch, who reported on the expedition to Point Barrow in the late 1800s, state that the Inuit, although they consume (or did at those times) a primarily meat diet, don’t eat more fat than the average American of the time.

This from Murdoch, who published it in the Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology in 1892, re the eating habits of the Eskimo:

This pretty much mirrors what Stefansson wrote about the Inuit diet based on his time with them. He observed their diet to be composed of 50 percent caribou, 30 percent fish, 10 percent seal meat, and the rest made up of polar bear, rabbits, birds and eggs.

Inland Inuit ate more caribou. Coastal Inuit ate more marine mammals. However, whale and seal meat are extremely lean. And Caribou meat is much leaner than beef or pork. Caribou is even leaner during the winter.

So, if they weren’t eating a lot of blubber, that would mean that they were high protein and low fat. If they were high fat, I think it would have to be mainly from blubber.

Actually, it depends upon what part of the caribou you’re eating. According to Stefansson, the older animals were favored because they had more fat, and the slab of back fat can weight out at 50 lbs. Plus, the marrow is much favored along with the head. So, although the meat itself is lean, there is plenty of fat to go around from a caribou.

Right, but a male caribou gets up to 400 pounds, so overall it’s a pretty lean animal. And some of the caribou fat was used for their lamps from what I understand. Cows and swine are much fattier animals for sure, as they are bred to be fat. Very interesting!

But I can see that whales and seals would definitely have yielded much more fat than a caribou.

The direct measurements were not “against ketosis”, they were equivocal about ketosis, because they were measuring acetoacetate. This is why I wrote about acetoacetate measures recently.

Thanks for this link. I should have put a link to this post in mine.

Thank you for the clarification L.Amber, the nature of the measurement is part of the rational for discounting it, if there’s any reason to think that they were in ketosis from their diet composition.

I firmly believe that if one is Homo sapien, one must struggle against cognitive dissonance until one drops dead.

Doubtlessly true.

According to Eli Pariser’s TED talk, Google and Yahoo (among others) are actively reinforcing our confirmation bias through the use of “algorithmic gatekeepers” that significantly restrict our search results. Check it out here if you have time, (it’s only 9 minutes)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B8ofWFx525s

Your example of people dismissing the idea of their favorite politician being a pedophile reminds me of people who look to athletes and other celebrities as role models. There’s nothing wrong with admiring someone’s ability as an athlete or actor or politician, but none of that means they have a good character. Maybe admiring someone for one thing and loathing them for something else causes cognitive dissonance in some people.

Information and a humble attitude are the main ways I avoid confirmation bias. Further information can show me where I’m wrong, and thinking about all the times I’ve been totally, completely wrong help me use that information.

The problem with confirmation bias is that, once you start looking for it, you find it everywhere!

Good article. Thanks.

Everything is relative, what a mosaic of metabolic factors we all are. I wish Richard and friends would bring Dr Richard Bernstein into this. T2DM at 72 y/o, zero carbs and glibly says he hadn’t touched a piece of fruit in 30 years…and not a single diabetic complication. …must be doing something right for him, anyway. Of course, “they” say he is secretly treating all his patients for autoimmune disease. Where did they google that? Considering all of this, I do think the area of microbiota and RS is fascinating and long overdue. I am an 80 y/o cardiologist, still working full time, never catch a cold, and have been LC for 40 years…but now I am taking 2 TBL BRMPS BID, checking my finger stick often and having a hell of an interesting time. Let’s all stay tuned and see where it takes us.

Actually, Richard Bernstein, who is a friend of mine, is a Type 1 diabetic and has been so since he was 12 years old. A fascinating guy who knows pretty much everything there is to know about DM. He would no doubt give RS a try, all the while keeping a close watch on his own blood sugars.

If you are 80 and still practicing cardiology, God bless you. You’re a better man than I am.

Keep me posted on your self experimentation. I’m keenly interested.

I hope they don’t bring Dr. Bernstein into it; they will just fling feces at him.

Their whole game is a blizzard of reference-spam, and if anyone doesn’t react with awe, they are then bullied in the nastiest possible aging-jock manner.

It’s an open sewer. I can’t for the life of me figure out why anyone reads it. But I guess there are a lot of people who don’t recognize bullying for the sign of weakness that it is.

Forgot to check the f/u boxes

Dr. Eades,

You are right that Duck has confirmation bias. But, so do you!

The problem is that you haven’t actually refuted any of Duck’s statements. You say that scientists flash freeze to -320, and while that may be true, he provided evidence of glycogen degradation stopping at -18ºC. You haven’t refuted that.

He provided evidence of significant carbohydrates in blubber and marine mammals as well as glycogen in beef after many days. You haven’t refuted that either.

You seem to have ignored those points.

Who cares? Assuming none of it is degraded, it’s not enough to matter. Look at the links I put up on the a couple of the previous comments.

I care. The temerature really matters. Lets turn to some science, for instance here:

“Glycogen debranching enzyme activity in the muscles of meat producing animals” (dissertation)

https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/20823/glycogen.pdf?sequence=2

The paper you linked is a nice one. Perhaps you should read it more closely. It describes well what goes on post mortem when muscle turns to meat.

As I said before, if we grant that there is a couple of grams of glycogen left per pound of meat, so what? It’s not enough to keep someone following such a diet out of ketosis.

“…there is a couple of grams of glycogen left per pound of meat…”

Indeed, so what?

If you grant that low number, it’s still for muscle meat of land mammals.

It doesn’t matter how little glycogen they may have had from land mammals if they were eating the much higher carb-containing marine mammals and blubber.

Is there some rationale that says the rate of degradation is faster in these sources such that they’d still end up with just a couple of grams per pound? Would need to cite that info.

That would be called an argument, btw, not ‘confirmation bias’.

However, nothing about glycogen matters if their diet was so high in protein from pounds of meat per day that they couldn’t develop a ketone-based metabolism.

Unless someone can show the Inuit didn’t eat blubber (!) and they didn’t eat pounds of meat per day, everything else is moot.

You wrote:

If you grant that low number, it’s still for muscle meat of land mammals.

It doesn’t matter how little glycogen they may have had from land mammals if they were eating the much higher carb-containing marine mammals and blubber.

Doesn’t jibe with my sources. Stefansson, for example, writes that during the years he lived with the Inuit, about half their intake came from caribou meat, 30 percent from fish, 10 percent seal meat and the remaining 10 percent from polar bear, rabbits, birds and eggs. This was confirmed by the report of the Schwatka expedition from 1878-1880 and from a report from a Siberian trek in the mid 1860s. Not a lot of blubber in the Inuit diet.

Stefansson writes in detail about the cuts of caribou prized by the Inuit. Mainly the fatty cuts. The head, to be specific,

In responses to previous comments, I’ve addressed the notion that the protein in meat prevent ketosis.

Thank you for the reference to Stefansson. So it’s back to which references to accept and which not.

How is that confirmation bias?

Only if one side is summarily dismissed or ignored is it any kind of bias.

Please don’t get me wrong, I really appreciate the effort you put in your blog, in informing and educating and in responding to comments. I often learn something new here and I know many people have been helped.

I thank you and I’m sure many have thanked you and for years!

But I have to say, I just don’t understand why you would write a post summarily dismissing as ‘confirmation bias’ all references that do not support ketosis in the Inuit.

You’ve been addressing some of those in the comments, I see. I’m really glad about that.

Having the discussion, reexamining old information in light of new information, it helps everyone learn no matter what were their starting biases, don’t you think?

I think you may have completely missed the point of my post. The post wasn’t written as an argument about whether or not the Inuit are in ketosis. I didn’t write it to stimulate a debate on that issue either here in the comments section or via dueling blog posts. As you may recall, I wrote that I had been meaning to put up a post about the confirmation bias for a long time, and that the Duck’s activities prodded me into it.

If you do as I suggested in the post and Google the words freezing stops glycogen as Duck did, you will find many pages of links to articles confirming the fact that glycogen degrades to lactic acid post mortem long before you ever get to the piece Duck used to confirm his bias. In other words, Duck passed over many articles refuting his own belief to get to the one confirming it, then accused me of not responding to the ‘science’ he had presented me with.

Whether he’s right or I’m right doesn’t matter. What he did was what all too many people do. He simply pawed through the data, ignoring what refutes his theory and seizing on that confirming it. Which is what inspired me to write the post.

About high protein inhibiting ketosis, I see your answer to someone above and will study it.

Meanwhile though, I thought the relative amount of glucagon-to-insulin drives metabolism towards gluconeogenesis or towards glycolysis.

Gluconeogenesis first ramps up during fasting as blood glucose drops because the glycogen stores drop and after that it’s running on muscle protein so gluconeogenesis scales down to preserve muscle protein.The scaling down is enabled by increasing ketone production.

With No fasting, gluconeogenesis will still ramp up enough to maintain blood glucose levels if there’s not enough from the diet, but after that where’s the drive to then lower gluconeogenesis if there’s no muscle break down, but rather, plenty of protein that can continue to fuel it?

I thought therefore that in the end, fat is the key to ketosis. That’s why whether a diet is ketogenic is determined by the relative proportion of fat to the other macros.

The ratio of insulin to glucagon drives the system toward glycolysis or gluconeogenesis. During fasting, insulin falls and glucagon rises, driving the system toward gluconeogenesis. Dietary protein increases insulin and glucagon, keeping the system on the gluconeogenesis path, just not as intensely. And with the dietary protein, structural protein isn’t wasted.

The key to ketosis is brain energy needs. If the brain needs energy and carbs aren’t available, then the liver breaks down as much fat – either dietary or body – as it needs to to provide the ketones to fill the gap.

I had read Stefansson’s work over 30 years ago and have much admired him. While LC or VLC is not for me, his hands on exploration and research are far more valuable than a mess of scientific papers.

I remember him writing that one time in the Arctic, they ran out of seal oil and only had lean seal meat to eat. They immediately fell ill and were rescued barely in time by some Inuit who gave them copious quantities of blubber. From then on, he made sure he had plenty of fat with his meals and told everyone who would listen, he was on a high FAT diet, not high protein.

Re: Inuit ketones,

The explanation possibly lies here: (forget the T1D) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15893109

Cold-adapted carnivores, e.g. dolphins. run “diabetic” BG on a “ketogenic” diet.

They are really good at gluconeogenesis, but because low insulin, no harm is done – just cryoprotection.

This might decrease ketones somewhat. Are there any BG readings from Inuit eating ketogenic diets?

Interesting. As I recall, the BS were normal in the papers cited in this post. But I haven’t gone back and checked.

Thanks for this post. I am always interested in seeing another angle on how easily we delude ourselves. Readers may also enjoy David McRaney’s site, youarenotsosmart.com. It’s also a book.

Thanks for the link. Interesting stuff.

Thank you for this post. Seems the FTA posse is out in force these days trying to intimidate and badger other bloggers that don’t agree with them. It has worked on some and I don’t read those blogs anymore. The guy that hides behind the moniker of ” duckdodger” will never answer questions regarding his credentials . He makes crazy claims and then ducks and dodges. If they really wanted to present information that could be of help to people their tatics leave something to be desired. Most of this is just an attempt to create hype for the upcoming book. It’s not the ” RS is great book”.

It’s the” anti LC book

Thomas Huxley put your eloquent post in this way:

By the way, I like your metaphor of rolling down a pyramid, might be even more powerful it you started at a mountain top in winter, and you (a pebble) began rolling down one side or the other. Somewhere toward the bottom, an avalanche starts, and the pebble still in the center is swept out to one of two oceans (forgetting the Arctic for the moment).

Duck belongs to a tribe of wing nuts, who are all too common these days. I agree that TV and the Internet have brought them out of the slime and woodwork.

Thanks for spending your valuable time in elegantly dissing Duck. Great fun for the rest of us.

I’ve a quick question too, I tend to get cramps most in my left leg. No one has mentioned a circulatory problem, but based on your description, is it possible I’m not getting enough blood to wash away the lactic acid? Oddly enough, I can ride a bike with no cramps, but running produces them, and they sometimes occur at nights.

Re the question. Difficult to tell given the small amount of info. Since you’re a reader of this blog, I assume you’re following a low-carb diet. If so, you might want to up your fluid intake and your sodium intake. And perhaps your potassium and magnesium intake. If all else fails, get your thyroid checked. Thyroid problems can sometimes result in bizarre musculoskeletal problems.

Read the first two links in this post for some additional info.

I’ve had back and forth comments with DuckDodgers myself, and he seems more concerned with wanting to be right, than actual truth. Everybody LC seems like an enemy to him, especially if they at all appear skeptical about RS.

Though I’m personally trying RS, and think it’s beneficial, some in the RS crowd want to turn everybody that advocates any type of LC diet into an enemy.

Dear Dr. Eades, thank you very much for the informative post. It’s not easy to do LC as there’s so much conflicting information floating around.

You stated:

“The Inuit burn ketones as they make them, so it stands to reason that they might not have measurable ketones under normal circumstances. ” 2 questions if you don’t mind, please:

1. You mean one can be in ketosis and not have measurable serum ketone level?

2. Drs. Phinney/Volek suggest optimal ketosis level of 1.5-3mM. What is your take on this?

Thanks again.

I’m going to copy a response to a previous comment that I just posted, so it wasn’t there when you wrote this comment.

Thank you, Dr. Eades, appreciate it.

What is your opinion on my 2nd question if you don’t mind.

I would say ketones at a level of 1.5-3mM would be fine. I’ve seen ketones up to almost 5mM without a problem. Phinney has done much of the work on ketosis and ketoadaptation, so I would tend to agree with him.

There is something that I have a question about. You say that the Inuit were keto-adapted to a near perfect degree, so that in normal conditions they had no measurable ketones. That seems plausible. But just one to two days of fasting had them producing measurable ketones? Why would that be? Wouldn’t their ketone producing and consuming systems just continue on as before? Wouldn’t the feedback from the ketone consuming tissues and the ketone producing tissues stay the same and maintain the previous balance? Why a sudden surplus? It seems rather, well, rather odd that the white bread eaters and the Inuit would have the same physiological reaction to the same intervention (fasting). Again, after a lifetime of being keto adapted how could just two days of fasting cause a need for a surplus? I can see why in someone not keto adapted, but what would be the need in someone who was? If they’d been functioning perfectly for many years at a certain level of ketone production why would that production ramp up in such a short time from such a benign intervention unless the Inuit actually were like the white bread eaters going into the fast? Puzzling….uh, depending on which side of the bias you’re on.

I’m glad you asked this question. I was hoping someone would. I actually started to write about this in the post, but the thing had gotten so long, I cut it out. And hoped someone would bring it up here.

When the Inuit consume their traditional diet composed of primarily fatty meat, they get a lot of fat and a moderate amount of protein. Their bodies use the fat for energy, with a bit being converted to ketones to replace some of the glucose required for glucose-dependent tissues. Assuming they are in equilibrium, their bodies should pretty much consume the ketones as they are produced.

The protein in their diet does two things: it replaces worn out proteins, and it converts to glucose in the liver via gluconeogenesis. This glucose is used for the brain and the other tissues that are glucose dependent. Plenty of protein means the body isn’t in starvation mode, and glucose can be made as needed.

During a prolonged fast, the brain derives a lot of its energy (~40 percent) from ketones, allowing the body to conserve muscle protein, which is the reservoir for glucose. At the start of the fast, the body breaks down muscle to make the glucose needed for glucose-dependent tissues. At the same time the body begins to rapidly breakdown body fat to get at the glycerol backbone of the stored fat to use for making glucose. Muscle is much more vital than fat, which is basically just stored energy, so the body makes the switch over as quickly as it can to minimize muscle breakdown.

The energy needs of the brain drive this process, so when the Inuit, who were eating fatty meat and using the fat and protein for energy and sugar, start to fast, they switch over to burning more body fat to access the glycerol than they really need to burn. This excess fat makes a pass through the liver where it is converted to ketones, and so ketone levels in the blood rise to measurable levels.

The truth is out there. My search bubble revealed the following estimate of diet of the 1855 Eskimo –

Protein (g) 282

Carbohydrate (g) 54

Fat (g) 135

Calories (Cal.) 2640

“It is, however, worth noting that according to the customary convention (Woodyatt, 1921 ; Shaffer, 1921) this diet is not

ketogenic since the ratio of ketogenic(FA) to ketolytic (G) aliments is 1.09”

From…. Sinclair Hm. The diet of Canadian Indians and Eskimos. Proc Nutr Soc 1953; 12: 69-82

The key of course is to keep searching beyond the references provided to support one side of an argument.

Confirmation bias is a rabbit hole that is very easy to fall into and really painful to get out of. Like you, I make it a point to force myself what blogs or news sites on the other side of the political spectrum are saying just to get a more balanced perspective on things.

Hi Dr. Mike.

I offer you and your readers what I hope is perceived at minimum, to be a rather gentle antithesis.

http://freetheanimal.com/2014/04/confirmation-landscape-dialectics.html

Cheers and good will, sir.

Cheers and good will back to you.

So – if I eat carbs at The Perfect Health Diet level and my last HA1C test was 5.2% – what would you say – that I’m a carb adapted human?

Nope. I might say you are a sort of carb-tolerant human, but that’s about as far as I would go. A 5.2% HgbA1c calculates to an average blood sugar of about 96, which I think is a little high. I would rather see HgbA1cs in the mid to high 4 range.

Dr. Eades,

Do you find many people achieve the mid to high 4 range via ketogenic diet alone or is insulin and/oradditional specific supplements necessary? Also, do you rely solely on the HgbA1C? Chris Kresser had an interesting piece on this: http://chriskresser.com/why-hemoglobin-a1c-is-not-a-reliable-marker

No, I don’t find many people with high ketone levels – most are in the lower ranges. But I wouldn’t go nuts if I saw a 5mM as long as glucose was normal.

I like the HgbA1c for diabetic patients because it gives a rough approximation of what the average blood sugars are for the previous few months. It’s not a perfect measure by any means, but I like it because patients can’t game it. Before the HgbA1c measurement became readily available, diabetic patients and those with glucose intolerance of not yet diabetic levels could eat low-carb or even fast the day before their office visit and show up with normal looking blood sugar levels. The HgbA1c put an end to that because if they show up with a blood glucose of 85 mg/dl and a HgbA1c of 6.8, as a doc, you know what’s going on.

Thank you so much for your kind response Dr Eades. I think I was unclear because the mid to high 4 range I was referring to was the HgbA1C test levels, not ketone levels. I wondered if you knew of how common it is for those following a ketogenic diet to get A1C levels to the mid to high 4 range without resorting to insulin.

Sorry for the confusion. Are you asking about diabetics or non-diabetics?

I’d like to know for non-diabetics. I have been practicing low carb/paleo on and off for a while now and finally have converted solely to low carb (after realizing that I don’t need carbs for exercise and for other reasons), but I doubt I could ever get my hemoglobin A1C into the 4 range. I just had a blood test, so I’ll see what it says after about 4 months of low carb.

Keep us all posted.

Well, the idiot doctor did not order a hemo A1C!! Fasting blood glucose was 103 (exactly the same as last year, when I was also low carbing for a while). I’ll need to get another blood test done. No vitamin D, either. I don’t know what she was thinking. Also, my TC was 179 and my HDL was 38. No matter what I do (exercise, fish oil, saturated fat, etc.), I can’t seem to get my HDL up. I’ve had around this level of TC and HDL since I’ve been 24 or so. My HDL was 42 last year, so it went down, but that’s probably within the range of accuracy of the measurement anyway.

We are not tweeters, but we enjoy following those that Dr. Mike shares on his blog.

When we suddenly came upon tweets about the Inuit and ketogenesis we wondered what this was all about. We first learned of the Inuit Eskimos and explorer Stefansson from the first edition of Protein Power many years ago. Intrigued by PP, we followed up on Stefansson and his studies, including specifics of the experiment at Bellevue Hospital in NYC. Details about Inuit nutrition, lifestyle, and health status are well documented, so why this fuss about whether they are in ketosis or not? (Many thanks for your clarification of the ketone lab findings in this “Beware the Confirmation Bias” post)

We decided to go to the post of FTA to see if we could learn the “what and why” of the dispute. No luck on that score, but it did become apparent that FTA believes (or wants his readers to believe) that Dr. Mike does not know everything and that Dr. Mike does not respect him and his ‘science.’ FTA’s lack of logical argument about Inuit ketosis led us to believe that he really does not care about persuading Dr. Mike but rather just wants to 1. Put a few pockmarks on a sterling reputation or 2. Promote FTA and increase readership.

We know you are not worried. PP speaks truth not opinion. Bless you and MD.

Thanks for writing. Good to hear from you guys. Enjoyed your post on metabolic energy control.

I’m sorry I was unclear. I’m was wondering about non-diabetics and diabetics not taking exogenous insulin. But maybe it doesn’t really matter because as you explained, the real value in the A1C is to get a clearer picture of what’s been happening over the previous few months rather than rely merely on the fasting test. I have to smile at your description of how diabetics can game the fasting glucose test because that’s just what my father used to do. He’d “get religion” a few days before the test and meticulously count his alloted carb units (in those days low carb was the recommended diet for diabetics) and fast extra long before the blood draw. My father was a slender type 2 so docs were just content to see a decent fasting without further inquiry into what gastronomical hijinks could have been happening during the prior months.

Okay, I struggled through your political metaphors and finally got to your point. I think.

I have to say, as someone who has lived on all parts of the political spectrum, I would recommend you find a new favorite site.

All of those links are crap. You won’t learn anything.

I find google etc. to be fun. As soon as I see something that makes sense, I google the other side.

Even your analysis of confirmation bias is pretty shallow, and oddly seems to be used to try to prove that your argument is better because you have less bias.(I am sure there is a logical fallacy in there) When in fact you have done little to support your argument.

I don’t care. I will draw my own conclusions, and since I don’t have a blog to promote I don’t have to prove my lack of bias.

However if your ignorance about what is a good source of information on politics/current events is any measure, then I don’t reckon you would be all that much better with science.

By the way, I respect the work you have done, but this article comes off as childishness disguised as scholarship from over here.

I find it odd that if the inuit were so carb dependant they had zero “atkins flu” when the carbs are removed via fasting or other intervention.

Seems they have bodies experienced at running on ketones.

In your article you provided a definition of a “real science”:

“In real science, which is, sadly, not practiced all that often, researchers attempt to discredit their hypotheses, not confirm them. Only after repeated efforts to prove their own theories incorrect, do true scientists start to consider that they may be on to something.”

Can you please show us, where in your article do you try to falsify, discredit, prove incorrect your hypothesis that Inuit are in ketosis?

I’m going to repeat to you what I wrote to another commenter yesterday:

So if

1) your hypothesis was that Duck Dogers has confirmation bias,

and

2) your definition of real science is “researchers attempt to discredit their hypotheses, not confirm them. Only after repeated efforts to prove their own theories incorrect, do true scientists start to consider that they may be on to something”

then where are your repeated attempts to prove false your hypothesis that Duck Dodgers has a confirmation bias?

I don’t have to because the simple pathway from glycogen to lactic acid has stood the test of time. All the enzymes involved are know, the reactions speeds are known, and how the whole process works from beginning to end has been elucidated and written up in countless papers and in every modern biochemistry text known. The process has gone from being an hypothesis to as close to a known fact as you can get.

If Duck is trying to refute this fact, then does my pointing this out mean I suffer from the confirmation bias?

If Duck were tell me that Inuit can flap their arms and fly, and I call BS on him, would you say I’m falling victim to the confirmation bias?

Ridiculous as it seems, that’s just about what he’s doing.

So your approach is that if the actual real-world measurments of a complex system don’t match deductions from the theory then we should refrain from doing “real science” and assume primacy of deductions from theory over the real-world measurments of a complex system (like an animal organism)?

Your deductions were based entirely on theories – “countless papers”, “biochemistry texts”.

Duck Dodgers based his view on direct measurments of the thing the debate is about – done either by meat industry (glucose level in time) or by explorers measuring ketone levels in the Inuit. In what way do you think measurments are wrong?